![]() Dancing and Religion

Dancing and Religion

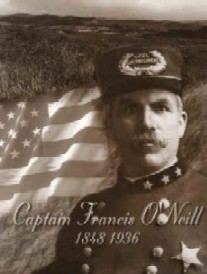

It is interesting to note that from earliest times, the relationship between religious authorities and dancing has been less than harmonious in almost all civilisations and societies. This has been the case from the time of the Old Testament, through early Christianity, medieval times and up to the first half of the twentieth century. It is said that in early Christian times its association with Pagan rituals was responsible. St Augustine was one of the early critics and some later writers believed that his descriptions of the drastic effects of dancing and associated practices indicate that he gained his knowledge through personal experience. One of the features of the Protestant reformation was the condemnation of most dances of the time. Many emerging Protestant countries banned dancing as the work and influence of the devil. It is said that in Scotland while the Reformed Church condemned dancing and dance music, particularly pipe music, the followers of Catholic and Episcopalian doctrines were less affected. The Calvinists denounced all dancing as evil and 'detrimental to the soul's future potential'. John Knox frowned on the introduction of French dances to the court by Mary, Queen of Scots.  According to Francis O'Neill [see photo], 'the Irish clergy were extremely moderate compared to their Scottish contemporaries'. The clergymen of the Scottish Free Church proclaimed with pride that they had 'burnt the last bagpipe and fiddle in the parish'. Duncan Fraser (in Scottish Traditional Dancing) complained that they had taken the colour out of people's lives. In England, after Henry VIII took control of the church, country dancing was revived. Henry himself was very much in favour of the good life, enjoying music, dancing and their associated pleasures. In Ireland, the Church authorities always seemed to view dancing as 'lewd, licentious, immoral and unbecoming to its flock'. There are many instances from the seventeenth century onwards, documented by Breandán Breathnach, where dancing, as well as the unfortunate pipers who were mainly held responsible for its popularity, was condemned. One of the reasons given was the association which existed at wakes, festivals, patterns and Sunday afternoon gatherings between music, dancing and drink, with its resulting improper behaviour. Ladies were

particularly likely to be denounced if they were known to favour dancing. Many bishops Dr Plunkett of Meath (1790?1819), Dr Bray of Cashel and Emly (1746) and Dr Moylan of Kerry (1785) condemned dance gatherings in their dioceses and threatened punishments, including excommunication, on those who dared disobey. Later, up to the 1930s, similar attitudes are recorded. There are numerous instances listed of musicians, who were held responsible for the dancing, being physically assaulted and their instruments broken and destroyed. One such victim, a piper named Stephen Ruane from Galway, was forced to abandon his livelihood as a professional musician and with no alternative way of surviving, he ended his days in the Galway workhouse.

According to Francis O'Neill [see photo], 'the Irish clergy were extremely moderate compared to their Scottish contemporaries'. The clergymen of the Scottish Free Church proclaimed with pride that they had 'burnt the last bagpipe and fiddle in the parish'. Duncan Fraser (in Scottish Traditional Dancing) complained that they had taken the colour out of people's lives. In England, after Henry VIII took control of the church, country dancing was revived. Henry himself was very much in favour of the good life, enjoying music, dancing and their associated pleasures. In Ireland, the Church authorities always seemed to view dancing as 'lewd, licentious, immoral and unbecoming to its flock'. There are many instances from the seventeenth century onwards, documented by Breandán Breathnach, where dancing, as well as the unfortunate pipers who were mainly held responsible for its popularity, was condemned. One of the reasons given was the association which existed at wakes, festivals, patterns and Sunday afternoon gatherings between music, dancing and drink, with its resulting improper behaviour. Ladies were

particularly likely to be denounced if they were known to favour dancing. Many bishops Dr Plunkett of Meath (1790?1819), Dr Bray of Cashel and Emly (1746) and Dr Moylan of Kerry (1785) condemned dance gatherings in their dioceses and threatened punishments, including excommunication, on those who dared disobey. Later, up to the 1930s, similar attitudes are recorded. There are numerous instances listed of musicians, who were held responsible for the dancing, being physically assaulted and their instruments broken and destroyed. One such victim, a piper named Stephen Ruane from Galway, was forced to abandon his livelihood as a professional musician and with no alternative way of surviving, he ended his days in the Galway workhouse. In his book, Notes from the Heart, P.J. Curtis relates how Junior Crehan, the well-known

Clare fiddler and source for some of the revived Clare sets, recalled a parish priest in the Thirties who was so opposed to music and dancing that he regularly prowled the country lanes at night in his efforts to stamp out these 'occasions of sin and debauchery'. On one occasion, on discovering a dance in full spate in a country house, he stormed the house, scattering the dancers with his blackthorn stick and, snatching a concertina [see photo] from the hands of a musician, ripped it apart, threw it on the fire and promised hell fire and damnation to all who had attended the dance. There are many similar stories told of clergymen turning up at dance gatherings, beating men or boys present and bringing girls home to their fathers, who were then encouraged to chastise them. Both the musicians and the dancers were likely to be denounced from the altar at Sunday Masses. The fear and general discomfort generated by this attitude from the clergy, who had such strong influence with Irish country people, contributed largely to the gradual disappearance of house and crossroad dances in rural Ireland. Many musicians are said to have emigrated and our Irish way of life was surely the poorer for their going. Francis O'Neill declared that 'no defensible reason, other than the defense of morality had ever been assigned for the hostility of Irish clergy to music and dancing'. This he found hard to justify, taking into consideration that the activities thus condemned were conducted publicly in the open, in houses, in fields, or at crossroads, among families, friends and neighbours. According to Breandàn Breathnach, the reasons for the church's concern was the grave danger threatened to traditional Irish standards of honour and modesty by foreign influences, as epitomised by the dancing of the time. In Lenten pastorals of 1925, parents and guardians were warned of their responsibilities for the preservation of the 'chivalrous honour of Irish boys and the Christian modesty of Irish maidens'. [...]

In his book, Notes from the Heart, P.J. Curtis relates how Junior Crehan, the well-known

Clare fiddler and source for some of the revived Clare sets, recalled a parish priest in the Thirties who was so opposed to music and dancing that he regularly prowled the country lanes at night in his efforts to stamp out these 'occasions of sin and debauchery'. On one occasion, on discovering a dance in full spate in a country house, he stormed the house, scattering the dancers with his blackthorn stick and, snatching a concertina [see photo] from the hands of a musician, ripped it apart, threw it on the fire and promised hell fire and damnation to all who had attended the dance. There are many similar stories told of clergymen turning up at dance gatherings, beating men or boys present and bringing girls home to their fathers, who were then encouraged to chastise them. Both the musicians and the dancers were likely to be denounced from the altar at Sunday Masses. The fear and general discomfort generated by this attitude from the clergy, who had such strong influence with Irish country people, contributed largely to the gradual disappearance of house and crossroad dances in rural Ireland. Many musicians are said to have emigrated and our Irish way of life was surely the poorer for their going. Francis O'Neill declared that 'no defensible reason, other than the defense of morality had ever been assigned for the hostility of Irish clergy to music and dancing'. This he found hard to justify, taking into consideration that the activities thus condemned were conducted publicly in the open, in houses, in fields, or at crossroads, among families, friends and neighbours. According to Breandàn Breathnach, the reasons for the church's concern was the grave danger threatened to traditional Irish standards of honour and modesty by foreign influences, as epitomised by the dancing of the time. In Lenten pastorals of 1925, parents and guardians were warned of their responsibilities for the preservation of the 'chivalrous honour of Irish boys and the Christian modesty of Irish maidens'. [...]

The commercial dancehalls were condemned as a cause of sin and scandal and a clamour raised for their control by the state. An article in The Irish Times in 1929 claimed that:

The clergy, judges and police were all in agreement concerning the baneful effect of drink and low dance halls. Further restrictions on the sale of drink, strict supervision of dance halls, the banning of all-night dances would abolish many inducements to sexual vice, but what was needed above all was recognition of the fact that the nation's proudest and most precious heritage was slipping from its grasp.

There would appear to have been a drive to establish state control and this came about with the Public Dance Halls Act of 1935, which required all public dances to be licensed and laid down the conditions under which licences might be issued by district justices. This act of the oireachtas was 'to make provision for the licensing, control, and supervision of places used for public dancing, and to make provision for other matters connected with the matters aforesaid'.

Some of the provisions of the act were as follows:

Article 1: In this act, the word 'place' means a building (including part of a building), yard, garden, or other enclosed place, whether roofed or not roofed and whether the enclosure and the roofing (if any) are permanent or temporary; the expression 'public dancing' means dancing which is open to the public and in which persons present are entitled to participate actively. [...]

While the passing of this act in itself had its merits, in relation to public dance halls of the day, the unfortunate thing was that country house dancing was included within the scope of the act. This meant that one needed a licence to hold a dance in a house where a gathering of people might come together. There is some doubt that the act was intended to stretch this far but the fact is that the civic guards and local clergy acted as if it did and the harassment they gave to those who held such social gatherings effectively put an end to them. In this way, a way of life in rural Ireland was gradually brought to a sad end. At the time, the country house dances were already under pressure from public dances in dance halls which were gaining popularity and where it would have seemed logical to preserve them as a real alternative to the public dances, they were instead penalised out of existence under the legislation. Now that dances could be controlled, parochial halls were built in most towns and villages to accommodate such dance gatherings as would be approved by the clergy. They seemed to approve of the more recently-formed céiĺ dances which had been largely put together by those in the Gaelic League who were members of its dancing section, the Irish Dancing Commission, formed in 1929. These céiĺ dances were praised for their modesty and strict formality. It was said that 'Irish dances do not make degenerates', the implication would appear to be that other kinds of dancing did.  Breandán Breathnach believes that the Public Dance Hall Act was enacted because of pressure on the government by some members of the hierarchy. He was concerned that as a researcher, he could not gain access to the government files on the subject. In searching for possible justification for the hostile attitude of both church and civil authorities to what was essentially a harmless pastime, there are few answers available. Francis O'Neill claimed that it was an attempt to preserve the morals of the nation. Breandàn Breathnach mentions that there may have been suspicion that the gatherings afforded a cloak to illegal, subversive organisations. If, as would appear more likely, the issue was a moral one, surely it was misguided to remove people from social gatherings at home, among their own friends and neighbours, and send them instead to licensed public dance halls which could hardly be expected to stop them straying into immoral ways. Another possible explanation mentioned by writers was that the income generated by the controlled dances was put into parish funds.

Breandán Breathnach believes that the Public Dance Hall Act was enacted because of pressure on the government by some members of the hierarchy. He was concerned that as a researcher, he could not gain access to the government files on the subject. In searching for possible justification for the hostile attitude of both church and civil authorities to what was essentially a harmless pastime, there are few answers available. Francis O'Neill claimed that it was an attempt to preserve the morals of the nation. Breandàn Breathnach mentions that there may have been suspicion that the gatherings afforded a cloak to illegal, subversive organisations. If, as would appear more likely, the issue was a moral one, surely it was misguided to remove people from social gatherings at home, among their own friends and neighbours, and send them instead to licensed public dance halls which could hardly be expected to stop them straying into immoral ways. Another possible explanation mentioned by writers was that the income generated by the controlled dances was put into parish funds.

![]()